Margaret Donaldson: Rethinking Child Development Theory

A Comprehensive Guide to Margaret Donaldson’s Theory for Students and Education Professionals

Margaret Donaldson’s work has profoundly impacted our understanding of child development and Early Years education. Her insights into how children think and learn have challenged traditional assumptions and reshaped pedagogical practices worldwide. For Early Years professionals, educators, and students alike, engaging with Donaldson’s ideas is essential for fostering a deeper understanding of young children’s remarkable cognitive capacities and creating learning environments that truly nurture their potential.

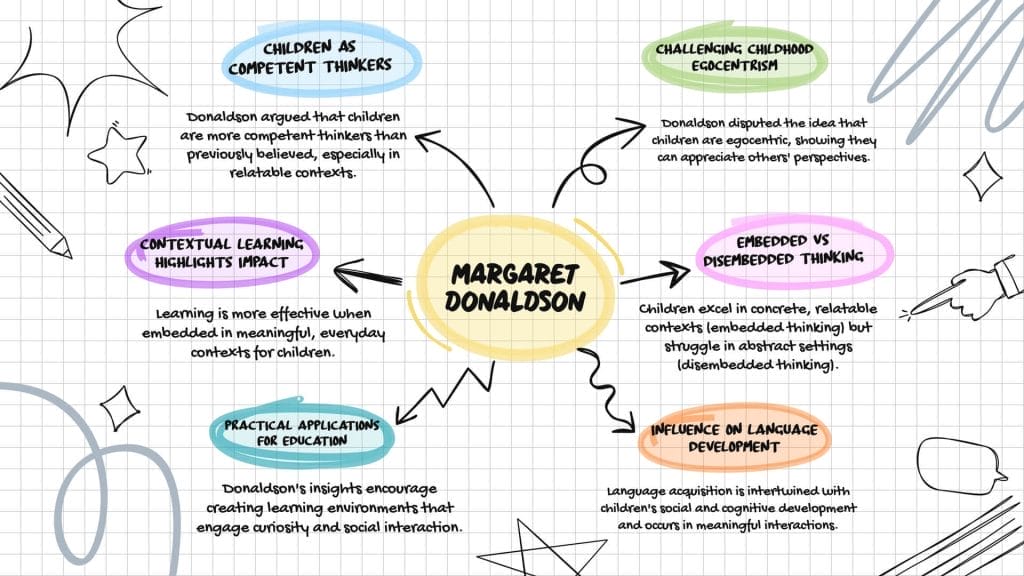

Brief Overview of Main Ideas

At the heart of Donaldson’s theory lies a fundamental insight: children are far more competent thinkers than previously believed, capable of reasoning, perspective-taking, and problem-solving when tasks are presented in meaningful, relatable contexts. Donaldson challenges the notion of childhood egocentrism, arguing that young children can understand others’ viewpoints when situations make “human sense” to them. She introduces the concept of embedded and disembedded thinking, highlighting the importance of helping children bridge the gap between their everyday experiences and the abstract, decontextualized demands of formal education.

Practical Applications and Benefits

Donaldson’s ideas have far-reaching implications for education practice. By creating learning experiences that engage children’s natural curiosity, build on their existing knowledge, and provide opportunities for social interaction and hands-on exploration, educators can support the development of critical thinking, language skills, and social understanding. Implementing Donaldson’s insights can lead to more child-centred, culturally responsive pedagogies that recognise and celebrate the diverse strengths and experiences of all learners.

This comprehensive guide delves into the life and legacy of Margaret Donaldson, exploring her key theories, research findings, and their enduring relevance for education. The article:

- Traces Donaldson’s intellectual journey and the historical context that shaped her work

- Examines her critiques of Piagetian theory and her alternative framework for understanding children’s cognitive development

- Highlights practical strategies for applying Donaldson’s ideas in real-world educational settings

- Considers the limitations and critiques of her work, and the ways in which subsequent research has built upon her contributions

- Provides an annotated list of recommended resources for further reading and professional development

Whether you are a seasoned practitioner or a student just beginning your journey in this field, engaging with Margaret Donaldson’s transformative ideas is an essential step in deepening your understanding of how young children learn and grow. By reading this in-depth guide, you will gain valuable insights and practical strategies for creating rich, responsive learning environments that honour the remarkable minds of the children in your care. So dive in, explore, and discover how Donaldson’s legacy can inspire and inform your own practice as an educator and advocate for children.

Download this Article as a PDF

Download this article as a PDF so you can revisit it whenever you want. We’ll email you a download link.

You’ll also get notification of our FREE Early Years TV videos each week and our exclusive special offers.

Introduction and Background

In the realm of Childhood Education, few figures have had as profound an impact as Margaret Donaldson, a pioneering Scottish developmental psychologist whose work challenged conventional ideas about children’s cognitive abilities. This article delves into Donaldson’s life, theories, and enduring legacy, exploring how her insights continue to influence our understanding of young minds and inform practices in Early Years settings.

Born on March 18, 1926, in Paisley, Scotland, Margaret Donaldson grew up in an intellectually stimulating environment that nurtured her curiosity about human development. After completing her undergraduate studies at the University of Edinburgh, she pursued a master’s degree in education and a doctorate in developmental psychology (Donaldson, 1992). These formative experiences laid the foundation for a remarkable career dedicated to unravelling the mysteries of children’s thinking.

Historical Context and Key Influences

Donaldson’s work emerged at a time when Jean Piaget’s theories dominated the field of developmental psychology. Piaget proposed that children progress through fixed stages of cognitive development, with each stage characterised by specific limitations in thinking abilities (Piaget, 1954). While Donaldson acknowledged the significance of Piaget’s contributions, she questioned some of his central assumptions, particularly regarding children’s egocentrism and inability to reason logically.

Donaldson’s thinking was also influenced by the work of Lev Vygotsky, who emphasised the role of social interaction and cultural context in cognitive development (Vygotsky, 1978). She drew upon Vygotsky’s ideas to argue that children’s thinking is deeply embedded in their everyday experiences and relationships, a perspective that would become central to her own theories.

Donaldson’s Key Concepts and Theories

Through her research and writings, Donaldson introduced several key concepts that challenged prevailing views of children’s cognitive capacities:

- Context and meaningful interaction: Donaldson argued that children’s thinking is best understood within the context of meaningful, real-world interactions rather than abstract laboratory tasks (Donaldson, 1978).

- “Human sense” and intentionality: She proposed that even young children are adept at making “human sense” of situations by interpreting the intentions and perspectives of others (Donaldson, 1978).

- Disembedded vs embedded thinking: Donaldson distinguished between “disembedded” thinking, which involves abstract reasoning isolated from real-life context, and “embedded” thinking, which is grounded in children’s everyday experiences and relationships (Donaldson, 1978).

These ideas formed the core of Donaldson’s critique of Piagetian theory and set the stage for a new understanding of children’s cognitive capabilities. In the following sections, we will explore these concepts in greater depth, examine the research that supported Donaldson’s claims, and consider the far-reaching implications of her work for Early Years education and practice.

Donaldson’s Key Theories and Ideas

Challenging Piaget’s Notion of Childhood Egocentrism

One of Margaret Donaldson’s most significant contributions to developmental psychology was her critique of Piaget’s concept of childhood egocentrism. According to Piaget, young children are inherently egocentric, unable to consider perspectives other than their own (Piaget, 1954). This egocentrism was thought to limit children’s ability to reason logically and engage in effective communication.

Donaldson challenged this view, arguing that children’s apparent egocentrism was more a function of the abstract, decontextualised tasks used in Piagetian research than a true reflection of their cognitive abilities (Donaldson, 1978). She designed experiments that presented problems in more meaningful, relatable contexts and found that even young children could demonstrate perspective-taking skills and logical reasoning when the tasks made “human sense” to them.

For example, in her famous “policeman doll” study with Martin Hughes, Donaldson asked children to hide a doll from a toy policeman, a task that required considering the policeman’s perspective. Children as young as three or four could successfully complete this task, suggesting that they were capable of decentering and understanding different points of view when the situation was framed in a familiar, engaging way (Donaldson, 1978).

Key Info:

- Donaldson and Hughes’ “Policeman Doll” study demonstrated that even preschool children can understand different perspectives when tasks are meaningful and engaging

- Children’s egocentrism may be more a result of abstract research tasks than a true cognitive limitation

- Recognising children’s early perspective-taking abilities has implications for how we communicate with and educate young children

The Role of Context and Social Interaction

Building on the work of Vygotsky (1978), Donaldson emphasised the crucial role of social context and interaction in children’s cognitive development. She argued that children’s thinking is intimately tied to their everyday experiences, relationships, and cultural background. From this perspective, understanding a child’s mental processes requires considering not just their individual cognitive abilities but also the social and cultural factors that shape their thinking.

Donaldson’s research highlighted how children’s performance on cognitive tasks could be significantly influenced by the way the tasks were framed and the social cues provided by adults (Donaldson, 1978). For example, she found that children’s responses to conservation tasks (evaluating whether quantities remain constant despite changes in appearance) could be improved by presenting the problems in a more naturalistic context or by changing the wording of the questions to make the intent clearer.

These findings underscored the importance of creating learning environments that are attuned to children’s social and cultural worlds, where new knowledge is presented in ways that connect with their existing understanding and experiences.

Key Info:

- Children’s thinking is deeply embedded in their social and cultural context, not just a product of individual cognitive development

- Cognitive abilities can be significantly influenced by how tasks are framed and the social cues provided

- Effective early education should create learning environments attuned to children’s social and cultural worlds

Embedded vs Disembedded Thinking

Central to Donaldson’s theory is the distinction between embedded and disembedded thinking (Donaldson, 1978). Embedded thinking is grounded in children’s direct experiences and interactions with the world around them. It involves reasoning about concrete situations, interpreting social cues, and making sense of events in terms of human intentions and relationships.

In contrast, disembedded thinking involves abstract reasoning that is divorced from immediate context. It requires stepping back from one’s own perspective, considering problems in a decontextualised way, and manipulating symbols or ideas independently of their real-world referents.

Donaldson argued that young children are highly skilled at embedded thinking but often struggle with disembedded thinking, particularly when problems are presented in artificial or abstract ways (Donaldson, 1978). This is not because they lack the cognitive capacity for logical reasoning, but because their thinking is so closely tied to their everyday experiences and interactions.

A key challenge for education, then, is to help children bridge the gap between embedded and disembedded thinking, gradually learning to reason about problems in more abstract, symbolic ways. Donaldson suggested that this could be accomplished by initially framing problems in meaningful contexts that connect with children’s existing knowledge and then progressively introducing more abstract elements as their understanding develops.

Key Info:

- Young children excel at reasoning about concrete, meaningful situations (embedded thinking) but may struggle with abstract, decontextualised problems (disembedded thinking)

- Moving from embedded to disembedded thinking is a key challenge of education, requiring a gradual introduction of abstraction

- Presenting new ideas in familiar, meaningful contexts can help bridge the gap between embedded and disembedded thinking

The Importance of Intention and “Human Sense”

Donaldson placed great emphasis on children’s ability to make “human sense” of situations by interpreting the intentions, goals, and perspectives of others (Donaldson, 1978). Even very young children, she argued, are acutely sensitive to social cues and can use their understanding of human behaviour to navigate complex social situations and solve problems.

This focus on intentionality and social understanding has important implications for education. It suggests that learning is most effective when it is embedded in meaningful social contexts, where children can draw on their intuitive understanding of human behaviour to make sense of new information and ideas.

Donaldson’s work also highlights the importance of clear communication and shared understanding between children and adults. When teachers are attuned to children’s perspectives and frame problems in ways that make intuitive sense to them, children are better able to engage with the material and demonstrate their true cognitive capacities.

Key Info:

- Even infants and toddlers can interpret intentions and use social understanding to navigate their world

- Effective learning environments engage children’s intuitive understanding of human behaviour and relationships

- Clear communication and attunement to children’s perspectives are essential for fostering shared understanding

Implications for Language Development

While Donaldson is perhaps best known for her research on children’s thinking, her ideas also have implications for language development. In contrast to theorists like Chomsky (1965) who emphasised the innate, language-specific capacities of the human mind, Donaldson argued that language acquisition is deeply intertwined with children’s general cognitive and social development.

From this perspective, children learn language not through a specialised “language acquisition device,” but by actively making sense of the speech they hear in the context of meaningful social interactions (Donaldson, 1978). They use their understanding of human intentions and relationships to interpret the communicative goals of others and gradually learn to express their own thoughts and ideas through language.

This view underscores the importance of rich, varied language experiences in the early years, where children have ample opportunities to engage in meaningful conversations and hear language used in a range of social contexts. It also suggests that language development is best supported when it is integrated with children’s everyday experiences and interests, rather than treated as a separate, decontextualised skill to be practiced in isolation.

Key Info:

- Language acquisition is intertwined with cognitive and social development, not a separate, innate module

- Children learn language by interpreting speech in meaningful social contexts, using their understanding of intentions and relationships

- Rich, varied language experiences embedded in everyday interactions are crucial for supporting language development

In summary, Margaret Donaldson’s theories offer a compelling alternative to traditional Piagetian views of children’s cognitive development. By emphasising the role of context, social interaction, and intentionality in children’s thinking, she challenges us to reconsider long-held assumptions about young children’s capacities and to create learning environments that are more closely attuned to their unique ways of making sense of the world.

Donaldson’s Research Approach

Designing Studies to Reveal Children’s Hidden Strengths

Margaret Donaldson’s research was characterised by a commitment to designing studies that could capture children’s true cognitive abilities, rather than their performance on artificial tasks. She recognised that many of the methods used in traditional developmental research, such as Piaget’s conservation experiments, often underestimated children’s capabilities by presenting problems in abstract, decontextualised ways that did not make intuitive sense to young minds (Donaldson, 1978).

In response, Donaldson and her colleagues at the University of Edinburgh developed a range of innovative research paradigms that aimed to study children’s thinking in more ecologically valid contexts. These studies typically involved:

- Presenting tasks in meaningful, relatable scenarios that engaged children’s natural interests and social understanding

- Using familiar materials and props to create a supportive, engaging context for problem-solving

- Framing questions and instructions in clear, simple language that aligned with children’s existing knowledge and expectations

- Observing children’s spontaneous behaviour and responses, rather than relying solely on verbal reports or forced-choice measures

By designing studies in this way, Donaldson was able to reveal cognitive strengths that had often been overlooked in previous research. Her findings challenged long-held assumptions about children’s egocentrism, inability to reason logically, and lack of perspective-taking skills, demonstrating that even young children are capable of sophisticated thinking when problems are presented in meaningful, supportive contexts.

The “Policeman Doll” Study: A Closer Look

One of Donaldson’s most famous studies, the “policeman doll” experiment (Donaldson, 1978), provides a clear example of her innovative research approach. In this study, children aged 3-5 were presented with a simple perspective-taking task that was framed as a hiding game.

The materials included:

- A toy policeman doll

- A toy “robber” doll

- A set of small walls arranged in a cross-shaped configuration

The child was told that the robber doll had stolen some money and was trying to hide from the policeman. The experimenter then placed the policeman doll at one end of the cross-shaped walls, facing away from the centre, and asked the child to hide the robber doll somewhere in the walls so that the policeman could not see him.

To succeed in this task, the child needed to consider the policeman’s perspective and choose a hiding spot that was occluded from his view. Donaldson found that even 3-year-olds could consistently solve this problem, demonstrating a level of perspective-taking skill that far exceeded what Piaget’s theory would predict.

The key features of this study that contribute to its effectiveness include:

- The use of familiar, engaging materials (dolls and simple props) that create a meaningful context for the task

- The framing of the problem as a hiding game, which aligns with children’s natural interests and social understanding

- The clear, simple instructions that make the goal of the task explicit and understandable to young children

- The focus on children’s spontaneous problem-solving behaviour, rather than relying on verbal explanations or justifications

By designing the study in this way, Donaldson was able to create a task that made “human sense” to young children and allowed them to demonstrate their true cognitive capabilities.

Key Takeaways

- Donaldson’s research aimed to study children’s thinking in ecologically valid contexts, using meaningful tasks and familiar materials

- The “policeman doll” study is a classic example of how framing problems in engaging, relatable ways can reveal children’s early cognitive strengths

- Donaldson’s approach emphasises the importance of social, cultural, and contextual factors in shaping children’s cognitive development

Practical and Current Applications

Bringing Donaldson’s Ideas into the Classroom

Margaret Donaldson’s theories have profound implications for how we approach early childhood education. By understanding the ways in which young children make sense of the world, we can create learning environments that harness their natural strengths and support their cognitive development. Here are some key strategies for applying Donaldson’s ideas in the classroom:

- Create meaningful contexts for learning: Donaldson’s work emphasises the importance of presenting new information and ideas in ways that connect with children’s existing knowledge and experiences. Teachers can do this by:

- Using familiar materials, stories, and scenarios as a starting point for exploration and problem-solving

- Framing activities around children’s interests and questions, rather than imposing abstract learning goals

- Making explicit links between classroom learning and children’s everyday lives, helping them see the relevance and application of new skills and concepts

- Encourage social interaction and collaboration: Recognising the central role of social context in children’s thinking, teachers should create ample opportunities for children to work together, share ideas, and learn from each other. This can involve:

- Facilitating small group activities and projects that require cooperation and communication

- Modeling effective social skills and problem-solving strategies during class discussions and activities

- Creating a supportive, inclusive classroom culture where all children feel valued and respected

- Use clear, simple language and instructions: To help children engage with new ideas and tasks, it is important to use language that aligns with their existing understanding and expectations. Teachers can support this by:

- Breaking down complex concepts into smaller, more manageable parts

- Using concrete examples and demonstrations to illustrate abstract ideas

- Providing explicit, step-by-step instructions for activities, with visual aids and prompts as needed

- Scaffold the transition from embedded to disembedded thinking: Donaldson’s distinction between embedded and disembedded thinking suggests that children need support to move from concrete, context-bound reasoning to more abstract, symbolic thinking. Teachers can facilitate this transition by:

- Beginning with hands-on, experiential learning activities that allow children to explore concepts in a concrete way

- Gradually introducing more abstract representations and symbols, such as charts, diagrams, or mathematical notation

- Explicitly discussing the links between concrete experiences and abstract ideas, helping children see the underlying concepts and relationships

- Embrace a holistic, integrated approach to learning: Rather than treating subjects like language, math, and science as separate domains, Donaldson’s work suggests that children learn best when these areas are integrated and connected to their everyday experiences. Teachers can support this by:

- Designing thematic units or projects that cut across traditional subject boundaries

- Encouraging children to use multiple modes of expression (e.g., drawing, writing, drama) to explore and communicate their ideas

- Providing opportunities for children to apply their skills and knowledge in authentic, real-world contexts

Ongoing Influences and Future Directions

Margaret Donaldson’s legacy continues to shape the field of early childhood education, both in terms of research and practice. Her emphasis on the social and contextual dimensions of children’s thinking has inspired a growing body of work on topics like collaborative learning (Rogoff, 1990), guided participation (Rogoff, 2003), and scaffolding (Wood et al., 1976).

In more recent years, researchers have also begun to explore how Donaldson’s ideas can inform our understanding of children’s thinking in specific content areas, such as science (Gelman & Brenneman, 2004), mathematics (Clements & Sarama, 2014), and literacy (Morrow, 1990). This work highlights the importance of designing learning experiences that build on children’s existing knowledge and interests while also introducing new concepts and skills in meaningful, developmentally appropriate ways.

As the field continues to evolve, there is a growing recognition of the need to create more inclusive, culturally responsive learning environments that honour the diverse strengths and experiences of all children (Ladson-Billings, 1995). Donaldson’s emphasis on understanding children’s thinking in context provides a strong foundation for this work, reminding us that effective teaching must always be grounded in a deep respect for children’s unique ways of making sense of the world.

Looking to the future, it is clear that Donaldson’s ideas will continue to shape research and practice in early childhood education. By embracing her vision of children as active, engaged learners who construct knowledge through meaningful interactions with the world around them, we can create educational environments that truly support the full range of children’s intellectual, social, and emotional needs. As we face the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century, Donaldson’s work remains an essential guide and inspiration for all those who care about the well-being and success of young children.

In summary, Margaret Donaldson’s theories have important practical implications for early childhood education, highlighting the need for learning environments that engage children’s natural curiosity, social understanding, and problem-solving skills. By creating meaningful contexts for learning, encouraging social interaction and collaboration, using clear and simple language, scaffolding the transition from embedded to disembedded thinking, and embracing a holistic approach to learning, teachers can help children build strong cognitive foundations.

Looking to the future, Donaldson’s legacy will continue to shape research and practice in early childhood education, reminding us of the importance of understanding and respecting children’s unique ways of making sense of the world. By embracing her vision of children as active, engaged learners, we can create educational environments that truly support the full range of their intellectual, social, and emotional needs.

Key Takeaways

- Donaldson’s theories suggest several key strategies for early childhood classrooms, including creating meaningful learning contexts, encouraging social interaction, using clear language, scaffolding abstract thinking, and embracing a holistic approach

- Real-world examples from preschool to primary classrooms illustrate how these strategies can be implemented in diverse settings

- Donaldson’s emphasis on the social and contextual dimensions of children’s thinking continues to inspire research on topics like collaborative learning, guided participation, and scaffolding

- As the field evolves, Donaldson’s work provides a foundation for creating more inclusive, culturally responsive learning environments that honor the diverse strengths and experiences of all children

Comparison with Other Theorists

To fully appreciate the significance of Margaret Donaldson’s contributions, it is helpful to situate her work in relation to other major figures in developmental psychology. By examining the similarities and differences between Donaldson’s theories and those of her contemporaries, we can gain a richer understanding of her unique perspective on children’s cognitive development.

Jean Piaget: Challenging the Notion of Childhood Egocentrism

As discussed earlier, much of Donaldson’s work was developed in response to the influential theories of Jean Piaget. While Donaldson acknowledged the importance of Piaget’s contributions, she challenged several key aspects of his model, particularly the notion of childhood egocentrism (Donaldson, 1978).

Piaget believed that young children are fundamentally egocentric, unable to consider perspectives other than their own. He argued that this egocentrism limits children’s ability to reason logically and communicate effectively, and that it is only overcome through a gradual process of cognitive development (Piaget, 1954).

Donaldson, in contrast, suggested that children’s apparent egocentrism is more a function of the abstract, decontextualized tasks used in Piagetian research than a true reflection of their cognitive abilities. Through her own studies, she demonstrated that even young children can show sophisticated perspective-taking skills when problems are presented in meaningful, socially embedded contexts (Donaldson, 1978).

This critique of Piaget’s work has important implications for how we view children’s thinking. Rather than seeing young children as inherently limited by their egocentrism, Donaldson’s perspective suggests that they are capable of more advanced reasoning when they can draw on their everyday knowledge and experiences.

However, it is important to note that Donaldson did not completely reject Piaget’s stage model of development. She acknowledged that there are important qualitative shifts in children’s thinking over time, even as she challenged some of Piaget’s specific claims about the nature and timing of these changes (Donaldson, 1978).

Read our in-depth article on Jean Piaget here.

Lev Vygotsky: The Role of Social Interaction and Culture

While Donaldson’s work is often framed as a response to Piaget, her emphasis on the social and cultural dimensions of cognitive development also bears important similarities to the theories of Lev Vygotsky.

Like Donaldson, Vygotsky stressed the central role of social interaction in children’s learning and development. He argued that children acquire new skills and knowledge through their participation in culturally meaningful activities, guided by more experienced partners such as parents, teachers, or peers (Vygotsky, 1978).

Vygotsky’s concept of the “zone of proximal development” – the gap between what a child can do independently and what they can achieve with support – resonates with Donaldson’s view of learning as a socially embedded process. Both theorists emphasize the importance of providing children with appropriately challenging tasks and the necessary scaffolding to help them succeed (Donaldson, 1978; Vygotsky, 1978).

However, there are also some notable differences between Vygotsky and Donaldson’s approaches. While Vygotsky focused primarily on the role of language and verbal interaction in cognitive development, Donaldson placed greater emphasis on the nonverbal, contextual factors that shape children’s thinking (Donaldson, 1978).

Additionally, Donaldson’s distinction between embedded and disembedded thinking – and her emphasis on the challenges of moving from concrete, context-bound reasoning to more abstract, symbolic thought – is not as central to Vygotsky’s theory.

Despite these differences, the commonalities between Donaldson and Vygotsky’s work highlight the growing recognition in the field of the social and cultural dimensions of cognitive development. Both theorists challenge us to move beyond a narrow focus on individual mental structures and processes, and to consider the complex web of relationships and experiences that shape children’s thinking.

Read our in-depth article on Lev Vygotsky here.

Jerome Bruner: The Importance of Meaning and Narrative

Another important point of comparison for Donaldson’s work is the theory of Jerome Bruner, who also emphasized the role of meaning and context in children’s cognitive development.

Like Donaldson, Bruner argued that children are active, constructive learners who seek to make sense of their experiences in terms of their existing knowledge and understanding. He stressed the importance of providing children with opportunities to explore and discover, rather than simply transmitting information through direct instruction (Bruner, 1961).

Bruner also placed great emphasis on the role of language and narrative in shaping children’s thinking. He suggested that the stories and explanations we use to make sense of the world serve as “templates” or “frames” that guide our perception and understanding (Bruner, 1990).

This focus on meaning and narrative resonates with Donaldson’s view of children as “human sense-makers” who actively interpret their experiences in terms of their social and cultural knowledge. Both theorists highlight the importance of creating learning environments that engage children’s natural curiosity and help them construct meaningful understandings of the world around them.

However, Bruner’s theory places somewhat greater emphasis on the role of symbolic representations and abstract thinking in cognitive development. While Donaldson stressed the challenges of moving from embedded to disembedded thought, Bruner saw this process as a key driver of intellectual growth (Bruner, 1966).

Despite this difference, the similarities between Bruner and Donaldson’s approaches underscore the importance of considering the meanings that children construct through their interactions with the world. By understanding the ways in which children make sense of their experiences, we can create educational environments that truly support their cognitive, social, and emotional development.

Read our in-depth article on Jerome Bruner here.

Implications for Early Childhood Education

The comparisons between Donaldson’s work and that of other major theorists highlight both the unique contributions of her perspective and the broader themes that unite different approaches to understanding children’s cognitive development.

By challenging Piaget’s notion of egocentrism, Donaldson helped shift the field towards a view of young children as more capable and sophisticated thinkers, particularly when they can draw on their everyday knowledge and experiences. This insight has important implications for early childhood education, suggesting that we should create learning environments that build on children’s natural strengths and interests.

At the same time, the commonalities between Donaldson’s work and that of Vygotsky and Bruner underscore the importance of the social, cultural, and meaning-making dimensions of children’s thinking. This suggests that effective early childhood education must go beyond a narrow focus on individual skills and abilities, and instead create opportunities for children to engage in collaborative, culturally relevant learning experiences.

Ultimately, by drawing on the insights of multiple theoretical perspectives, early childhood educators can create rich, supportive learning environments that honour the complexity and diversity of children’s cognitive development. By understanding the ways in which children actively construct meaning through their interactions with the world around them, we can help them build the strong foundations they need for lifelong learning and success.

In summary, comparing Margaret Donaldson’s theories to those of other influential figures in developmental psychology helps situate her unique contributions within the broader landscape of the field. While Donaldson is perhaps best known for her critique of Piaget’s notion of childhood egocentrism, her work also bears important similarities to the sociocultural perspective of Vygotsky and the meaning-centered approach of Bruner.

By emphasising how children actively make sense of their experiences through their everyday interactions and cultural knowledge, Donaldson challenges us to create early childhood learning environments that honour the richness and complexity of young children’s thinking. At the same time, by drawing connections to other major theoretical frameworks, her work underscores the importance of taking a holistic, integrative approach to understanding and supporting children’s cognitive development.

Key Takeaways

- Donaldson’s critique of Piaget’s notion of childhood egocentrism helped shift the field towards a view of young children as more capable thinkers, particularly when they can draw on everyday knowledge and experiences.

- Donaldson’s emphasis on the social and cultural dimensions of cognitive development bears important similarities to Vygotsky’s sociocultural perspective.

- Like Bruner, Donaldson stressed the importance of meaning and narrative in shaping children’s thinking, although she placed greater emphasis on the challenges of moving from embedded to disembedded thought.

- By drawing on the insights of multiple theoretical perspectives, early childhood educators can create rich, supportive learning environments that honor the complexity and diversity of children’s cognitive development.

Limitations and Criticisms

While Margaret Donaldson’s work has significantly advanced our understanding of children’s cognitive development, it is important to acknowledge and examine some of the limitations and criticisms of her theories.

Generalisability of Findings

Donaldson’s research, such as the “policeman doll” study, involved small samples of children from specific cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds, raising questions about the generalizability of her findings.

- Social scripts and expectations shaping children’s understanding of authority figures may vary across communities

- Highly structured, adult-designed tasks might not fully reflect real-world problem-solving challenges

- More diverse samples and naturalistic methods are needed to build a comprehensive understanding

Individual Differences

Donaldson’s emphasis on social and contextual factors may underestimate the impact of individual differences, such as temperament, personality, and experiences, on children’s learning.

- Variations in executive function skills (e.g., attentional control, inhibitory control, working memory) affect cognitive task performance

- Prior knowledge and experiences can influence problem-solving strategies

- An integrative approach considering both contextual factors and individual differences is needed

Need for Longitudinal Studies

Much of Donaldson’s research relies on cross-sectional designs, which do not fully capture the dynamic, ongoing process of cognitive development.

- Longitudinal studies following children over extended periods can provide insights into developmental trajectories and factors supporting or hindering growth

- Long-term impacts of educational approaches and interventions need to be investigated

- Building a stronger evidence base for practices and policies that best support cognitive development requires a long-term perspective

Integration of Cognitive and Affective Dimensions

Donaldson’s theories primarily focus on cognitive dimensions of development, without extensively exploring the role of emotions, interests, and values in shaping children’s learning.

- Affective and motivational factors, such as autonomy, relatedness, competence, and personal interest, drive children’s thinking and behaviour

- Integrating cognitive insights with research on emotional and motivational processes can lead to a more holistic understanding

- Early childhood education should nurture both cognitive and affective development to support positive, lifelong learning dispositions

Acknowledging these limitations and critiques allows for a more nuanced understanding of Donaldson’s contributions and highlights areas for further research and theoretical integration. By continuing to build upon her ideas while considering alternative perspectives and methodologies, researchers and educators can advance our understanding of how to best support children’s cognitive and overall development.

Conclusion

Margaret Donaldson’s groundbreaking work has left an indelible mark on our understanding of children’s cognitive development and early childhood education. Her influential book, Children’s Minds, challenged the prevailing Piagetian view of young children as egocentric and illogical, instead revealing their remarkable capacity for perspective-taking, problem-solving, and meaning-making when tasks are presented in familiar, socially meaningful contexts.

By emphasising the role of social interaction, cultural context, and real-world experiences in shaping children’s thinking, Donaldson’s theories have helped to shift the focus of developmental psychology from isolated mental structures to the rich, dynamic interplay between individuals and their environments. Her distinction between embedded and disembedded thinking has shed light on the challenges children face as they learn to reason about problems in more abstract, decontextualised ways, and has highlighted the need for educational approaches that bridge the gap between these two modes of thought.

Donaldson’s ideas have not only influenced academic research but have also had far-reaching implications for early childhood education. Her work has encouraged educators to create learning environments that engage children’s natural curiosity, build on their existing knowledge and experiences, and provide opportunities for collaborative, hands-on exploration. By recognizing children as active, competent learners who construct meaning through their interactions with the world, Donaldson has helped to shape a more respectful, child-centered approach to early education.

At the same time, it is important to acknowledge the limitations and critiques of Donaldson’s theories, which highlight areas for further research and theoretical integration. Questions remain about the generalizability of her findings to diverse populations and real-world contexts, the role of individual differences in cognitive development, and the need for longitudinal studies to better understand the long-term trajectories of children’s thinking. Additionally, integrating Donaldson’s cognitive insights with research on affective and motivational processes could yield a more holistic understanding of children’s development and learning.

Despite these limitations, Donaldson’s legacy continues to inspire and inform the work of researchers and educators around the world. Her emphasis on the social and contextual dimensions of cognition, her challenge to assumptions about young children’s capabilities, and her advocacy for learning environments that nurture children’s natural sense-making abilities remain as relevant today as they were when Children’s Minds was first published.

As we look to the future of early childhood education, Donaldson’s ideas will undoubtedly continue to shape our understanding of how young children learn and grow. By building on her insights and integrating them with new research and perspectives, we can create educational experiences that truly honour the complexity, creativity, and potential of every child.

Ultimately, Margaret Donaldson’s work reminds us that children are not simply empty vessels to be filled with knowledge, but active, engaged learners who make sense of the world in their own unique ways. By creating learning environments that respect and nurture this sense-making process, we can help all children develop the cognitive, social, and emotional skills they need to thrive in an ever-changing world. In this way, Donaldson’s legacy will continue to shape the lives of generations of children to come, inspiring us to see the remarkable minds that lie behind their bright, curious eyes.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Who was Margaret Donaldson?

Margaret Donaldson (1926-2020) was a prominent Scottish developmental psychologist who made significant contributions to our understanding of children’s cognitive development. She was a Professor Emeritus of Developmental Psychology at the University of Edinburgh and authored several influential books, including “Children’s Minds” (1978).

2. What was Margaret Donaldson’s theory?

Donaldson’s theory emphasized the role of context and social interaction in children’s cognitive development. She argued that children are much more competent thinkers than Jean Piaget had suggested, and that their abilities are best demonstrated when tasks are presented in meaningful, familiar contexts. Donaldson challenged Piaget’s notion of childhood egocentrism, suggesting that children can understand different perspectives when problems are framed in a way that makes human sense to them.

3. What is the main idea of Donaldson’s book “Children’s Minds”?

In “Children’s Minds,” Donaldson presents her critique of Piaget’s theory and offers an alternative view of children’s cognitive development. The main idea is that children are active, motivated learners who make sense of the world through their social interactions and real-life experiences. Donaldson argues that traditional research tasks often underestimate children’s true abilities by presenting problems in abstract, decontextualized ways.

4. How did Donaldson’s theory differ from Piaget’s?

While Piaget believed that young children are fundamentally egocentric and limited in their logical reasoning, Donaldson challenged these assumptions. She demonstrated that children can show sophisticated perspective-taking and problem-solving skills when tasks are embedded in familiar, meaningful contexts. Donaldson also placed greater emphasis on the role of social interaction and cultural context in shaping cognitive development.

5. What is the concept of “embedded” and “disembedded” thinking in Donaldson’s work?

Donaldson distinguished between two modes of thinking: embedded and disembedded. Embedded thinking is grounded in familiar, real-world contexts and involves reasoning about concrete situations, interpreting social cues, and making sense of human intentions. Disembedded thinking, on the other hand, involves abstract reasoning that is decontextualized from immediate experience. Donaldson argued that young children excel at embedded thinking but often struggle with disembedded thinking, which is more typically demanded in formal educational settings.

6. What was the “policeman doll” study, and why was it significant?

The “policeman doll” study was one of Donaldson’s most famous experiments, designed to test children’s perspective-taking abilities. In this study, children were asked to hide a doll from a toy policeman by placing it in a specific location within a model landscape. Donaldson found that even very young children (aged 3-5) could successfully complete this task, demonstrating an understanding of the policeman’s perspective. This study challenged Piaget’s claims about childhood egocentrism and showed that children’s cognitive abilities are often underestimated when tasks are presented in abstract, unfamiliar ways.

7. How has Donaldson’s work influenced early childhood education?

Donaldson’s theories have had a significant impact on early childhood education, highlighting the importance of creating learning environments that engage children’s natural curiosity and build on their existing knowledge and experiences. Her work has encouraged educators to use more contextualized, hands-on teaching methods and to view children as active, competent learners. Donaldson’s ideas have also influenced the design of educational programs and curricula that aim to bridge the gap between embedded and disembedded thinking.

8. What criticisms have been made of Donaldson’s research?

Some researchers have questioned the generalizability of Donaldson’s findings, noting that her studies often involved small samples of children from specific cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds. There are also concerns that the highly structured, adult-designed tasks used in her experiments may not fully reflect the challenges children face in real-world problem-solving. Additionally, some critics argue that Donaldson’s theory does not adequately address individual differences in cognitive development or the role of affective and motivational factors in learning.

9. How does Donaldson’s theory compare to Vygotsky’s sociocultural approach?

Donaldson’s emphasis on the social and contextual dimensions of cognitive development bears some similarities to Lev Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory. Both researchers stressed the importance of social interaction and cultural context in shaping children’s thinking and learning. However, while Vygotsky focused primarily on the role of language and adult guidance in cognitive development, Donaldson placed greater emphasis on the child’s active role in making sense of their experiences and the challenges of moving from embedded to disembedded thinking.

10. What is Donaldson’s legacy in the field of developmental psychology?

Margaret Donaldson’s work has left a lasting impact on the field of developmental psychology and early childhood education. Her theories challenged traditional assumptions about children’s cognitive capabilities and highlighted the importance of considering the social, cultural, and contextual factors that shape learning and development. Donaldson’s ideas have inspired generations of researchers and educators to create more child-centered, experiential learning environments that nurture children’s natural sense-making abilities. Her legacy continues to influence contemporary research and practice, reminding us of the remarkable competencies of young minds and the importance of fostering their growth through meaningful, engaging interactions with the world around them.

References

- Bruner, J. S. (1961). The act of discovery. Harvard Educational Review, 31, 21-32.

- Bruner, J. S. (1966). Toward a theory of instruction. Harvard University Press.

- Bruner, J. S. (1990). Acts of meaning. Harvard University Press.

- Carlson, S. M., & Moses, L. J. (2001). Individual differences in inhibitory control and children’s theory of mind. Child Development, 72(4), 1032-1053.

- Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax. MIT Press.

- Clements, D. H., & Sarama, J. (2014). Learning and teaching early math: The learning trajectories approach (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 135-168.

- Donaldson, M. (1978). Children’s minds. Fontana Press.

- Donaldson, M. (1987). The origins of inference. In J. Bruner & H. Haste (Eds.), Making sense: The child’s construction of the world (pp. 97-107). Methuen.

- Donaldson, M. (1992). Human minds: An exploration. Allen Lane/Penguin Press.

- Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 109-132.

- Flavell, J. H., Miller, P. H., & Miller, S. A. (2002). Cognitive development (4th ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Gelman, R., & Brenneman, K. (2004). Science learning pathways for young children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 19(1), 150-158.

- Grammer, J., Coffman, J. L., & Ornstein, P. (2013). The effect of teachers’ memory-relevant language on children’s strategy use and knowledge. Child Development, 84(6), 1989-2002.

- Grolnick, W. S., & Ryan, R. M. (1987). Autonomy in children’s learning: An experimental and individual difference investigation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(5), 890-898.

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory into Practice, 34(3), 159-165.

- Light, P. (1986). Context, conservation and conversation. In M. Richards & P. Light (Eds.), Children of social worlds: Development in a social context (pp. 170-190). Harvard University Press.

- McGarrigle, J., & Donaldson, M. (1974). Conservation accidents. Cognition, 3(4), 341-350.

- Meadows, S. (1996). Parenting behaviour and children’s cognitive development. Psychology Press.

- Morrow, L. M. (1990). Preparing the classroom environment to promote literacy during play. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 5(4), 537-554.

- Piaget, J. (1954). The construction of reality in the child. Basic Books.

- Richardson, K. (1998). Models of cognitive development. Psychology Press.

- Rogoff, B. (1990). Apprenticeship in thinking: Cognitive development in social context. Oxford University Press.

- Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. Oxford University Press.

- Rothbart, M. K., & Bates, J. E. (2006). Temperament. In W. Damon, R. Lerner, & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 99-166). Wiley.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78.

- Siegler, R. S. (1996). Emerging minds: The process of change in children’s thinking. Oxford University Press.

- Siraj-Blatchford, I., & Sylva, K. (2004). Researching pedagogy in English pre-schools. British Educational Research Journal, 30(5), 713-730.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

- Wellman, H. M., & Gelman, S. A. (1992). Cognitive development: Foundational theories of core domains. Annual Review of Psychology, 43, 337-375.

- Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(2), 89-100.

Further Reading and Research

Recommended Articles

- Grieve, R., & Hughes, M. (1990). An experimental investigation of the effects of structured discussion in group problem-solving. Early Child Development and Care, 60(1), 77-87.

- Hughes, M. (1975). Egocentrism in preschool children. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Edinburgh University.

- Hughes, M., & Donaldson, M. (1979). The use of hiding games for studying the coordination of viewpoints. Educational Review, 31(2), 133-140.

- Light, P. (1979). The development of social sensitivity: A study of social aspects of role-taking in young children. Cambridge University Press.

- Light, P., Buckingham, N., & Robbins, A. H. (1979). The conservation task as an interactional setting. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 49(3), 304-310.

- McGarrigle, J., Grieve, R., & Hughes, M. (1978). Interpreting inclusion: A contribution to the study of the child’s cognitive and linguistic development. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 26(3), 528-550.

Suggested Books

- Donaldson, M. (1992). Human minds: An exploration. Allen Lane/Penguin Press.

- In this book, Donaldson further develops her ideas about the role of context and social interaction in cognitive development, drawing on research from a range of disciplines including psychology, anthropology, and linguistics.

- Garton, A. F. (2004). Exploring cognitive development: The child as problem solver. Blackwell Publishing.

- This book provides a comprehensive overview of cognitive development from infancy to adolescence, with a focus on problem-solving skills. It includes a chapter dedicated to Donaldson’s work and its implications for understanding children’s thinking.

- Light, P., & Butterworth, G. (Eds.). (1992). Context and cognition: Ways of learning and knowing. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- This edited volume brings together contributions from leading researchers in the field of cognitive development, exploring the role of context in children’s learning and understanding. Several chapters draw on Donaldson’s ideas and their application in different areas of research.

- Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. Oxford University Press.

- In this influential book, Rogoff draws on sociocultural theories to argue for a more contextualized, culturally embedded understanding of cognitive development. Her work builds on many of the themes emphasized in Donaldson’s research, particularly the importance of social interaction and participation in culturally meaningful activities.

Recommended Websites

- The British Psychological Society (BPS) – Developmental Psychology Section: https://www.bps.org.uk/member-microsites/developmental-psychology-section

- The BPS Developmental Psychology Section provides resources and information for researchers, practitioners, and students interested in child development. The site includes news, events, publications, and links to relevant organizations and resources.

- The Jean Piaget Society: https://piaget.org/

- The Jean Piaget Society is an international organization dedicated to the study of cognitive development and constructivism. While focused primarily on Piaget’s work, the society’s website includes resources and information relevant to Donaldson’s theories, including conference proceedings, publications, and links to related research projects.

- The Society for Research in Child Development (SRCD): https://www.srcd.org/

- SRCD is a professional organization for researchers, practitioners, and students interested in child development. The society’s website includes a wealth of resources, including publications, policy briefs, and information about training and career development opportunities.

- Zero to Three: https://www.zerotothree.org/

- Zero to Three is a nonprofit organization dedicated to supporting the healthy development of infants and toddlers. The organization’s website includes a range of resources for parents, caregivers, and early childhood professionals, including articles, videos, and podcasts on topics related to cognitive, social, and emotional development in the early years.

Download this Article as a PDF

Download this article as a PDF so you can revisit it whenever you want. We’ll email you a download link.

You’ll also get notification of our FREE Early Years TV videos each week and our exclusive special offers.

To cite this article use:

Early Years TV Margaret Donaldson: Rethinking Child Development Theory. Available at: https://www.earlyyears.tv/margaret-donaldson-child-development-theory (Accessed: 29 May 2025).