Little Albert Experiment: Classic Conditioning Study Explained

Key Takeaways

- Classical Conditioning Demonstration: The Little Albert experiment showed how a 9-month-old infant could be conditioned to fear a white rat by pairing it with a loud noise, demonstrating that emotional responses can be learned through association.

- Ethical Violations: By today’s standards, the study committed serious ethical breaches including lack of informed consent, deliberately causing distress to a vulnerable participant, and failure to decondition the fear response.

- Methodological Limitations: The experiment had significant flaws including single-subject design, lack of controls, subjective measurements, and recent reanalysis of film footage suggests the conditioned fear may have been weaker than reported.

- Historical Significance: Despite its ethical and methodological problems, the study profoundly influenced behaviorist psychology and our understanding of how fears might develop, while also contributing to the evolution of research ethics.

What Was the Little Albert Experiment? Key Facts & Background

A 9-month-old baby, a white rat, and a loud noise behind his head. These simple elements combined to create one of the most influential and ethically troubling studies in psychology’s history.

The Little Albert experiment was conducted by John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner at Johns Hopkins University between 1919 and 1920. This famous study aimed to provide experimental evidence that classical conditioning—a concept previously demonstrated in animals by Ivan Pavlov—could also apply to humans (Watson & Rayner, 1920).

The experiment’s subject was a 9-month-old boy known as “Little Albert” (later identified as possibly William Albert Barger), who was described as “remarkably stable” and unusually fearless. Watson and Rayner’s experiment sought to answer three critical questions:

- Could an infant be conditioned to fear an animal that appears simultaneously with a loud, fear-arousing sound?

- Would such fear transfer to other animals or inanimate objects?

- How long would such fears persist?

The significance of this study stems from its position as one of the earliest demonstrations of how emotional responses—particularly fear—can be learned through conditioning rather than being innate. Despite being conducted over a century ago, the Little Albert experiment remains one of psychology’s most discussed cases, both for its findings and for the serious ethical issues it raises.

What Actually Happened to Little Albert?

Initially, Albert showed no fear of a white rat presented to him. However, Watson and Rayner discovered that a loud noise produced by striking a steel bar with a hammer behind Albert’s head reliably triggered a fear response.

Over several sessions, they paired the presentation of the rat with the startling noise. After just seven pairings across two conditioning sessions, Albert developed a fear response to the rat alone—crying and attempting to crawl away whenever it was presented, even without the accompanying noise.

This process demonstrated how a neutral stimulus (the rat) could become a conditioned stimulus that produced a fear response after being paired with an unconditioned stimulus (the loud noise) that naturally produced fear.

For modern psychology students, understanding this experiment is essential not only for grasping the principles of classical conditioning but also for developing critical thinking about research ethics and methodology in psychological science.

Note: While examining this landmark study in detail, it’s important to remember that by today’s ethical standards, this experiment would never be approved due to the intentional infliction of distress on an infant without informed consent or proper follow-up care.

Watson & Rayner’s Research Goals: The Three Critical Questions

John B. Watson, a pioneering behavioral psychologist, sought to establish behaviorism as psychology’s dominant theoretical framework. Watson believed that all human behavior could be explained through conditioning—a radical departure from the introspective approaches popular at the time (Watson, 1913).

Watson and his graduate student Rosalie Rayner designed the Little Albert experiment to demonstrate that emotional responses, including fear, could be conditioned in humans just as Pavlov had shown with dogs. Their study aimed to answer three fundamental questions that remain relevant to psychology students today:

- Can fear be conditioned in infants? Could an infant learn to fear a previously neutral stimulus (like a white rat) when it’s paired with a frightening sound?

- Does conditioned fear transfer to similar stimuli? Would Albert’s fear of the rat generalize to other furry objects—demonstrating stimulus generalization?

- How persistent are conditioned emotional responses? Would Albert’s conditioned fear last over time, or would it fade without reinforcement?

These research questions directly challenged the prevailing view that emotions were innate and unchangeable. Watson was determined to prove that environmental conditioning—not heredity or instinct—was the primary force shaping human behavior and emotional development.

EXAM TIP: When discussing the Little Albert study, always connect it to Watson’s broader theoretical goals. Examiners expect students to explain how this experiment supported Watson’s behaviorist view that all behavior is learned through conditioning rather than being innate or instinctual. This demonstrates your understanding of the study’s historical context and significance.

Background and Historical Context

The Little Albert experiment took place within a specific historical and scientific context that shaped its design and impact:

- The study was conducted at Johns Hopkins University between 1919 and 1920, during behaviorism’s early development

- It built directly upon Ivan Pavlov’s classical conditioning research with dogs

- Watson had recently published his influential “Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It” manifesto (1913), positioning behaviorism as an objective science

- The experiment occurred before the establishment of ethical guidelines for human research

- Watson was motivated to prove that environmental factors (nurture), not heredity (nature), determine human behavior

For Watson, Little Albert wasn’t just a test subject—he was living proof that human emotions could be manipulated through conditioning, supporting Watson’s controversial claim that he could take any healthy infant and “train him to become any type of specialist” regardless of the child’s talents or ancestry.

Experimental Procedure: How Little Albert Was Conditioned

Watson and Rayner’s experiment followed a systematic procedure designed to test their conditioning hypotheses. The subject, “Little Albert,” was approximately 9 months old when the study began—an age chosen because he was old enough to display emotional responses but young enough that he hadn’t developed many fears.

Session-by-Session Breakdown

The experiment unfolded across six distinct sessions over approximately four months:

| Session | Albert’s Age | Key Events |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 months, 26 days | Baseline testing with rat, rabbit, dog, monkey, masks, cotton wool, and burning newspapers. Albert showed no fear of any stimuli. |

| 2 | 11 months, 3 days | Initial conditioning: Rat paired with loud noise (two pairings). |

| 3 | 11 months, 10 days | More conditioning: Test with rat alone showed mild fear. Rat paired with loud noise (five more pairings). Second test with rat alone showed strong fear. |

| 4 | 11 months, 15 days | Generalization testing: Tests with rat, rabbit, dog, fur coat, cotton wool, and various hair samples (Watson’s, observers’). |

| 5 | 11 months, 20 days | Additional conditioning and room change: Tests in original room and a new room; extra conditioning with rat; new conditioning trials with rabbit and dog. |

| 6 | 12 months, 21 days | Final testing: Tests with Santa Claus mask, fur coat, rat, rabbit, and dog. Albert was discharged from hospital this day. |

The Conditioning Process in Detail

At baseline, Albert showed interest in, but no fear of, the white rat. However, he did display a natural fear response to a loud noise created by striking a steel bar with a hammer behind his head.

The conditioning procedure involved:

- Presentation of neutral stimulus: Albert was shown the white rat (initially a neutral stimulus that caused no fear)

- Pairing with unconditioned stimulus: As Albert reached for the rat, the researchers struck the steel bar with a hammer behind his head, producing a loud noise (the unconditioned stimulus)

- Repetition: This pairing was repeated seven times across two conditioning sessions

- Testing: Albert was then presented with the rat alone to see if it now elicited a fear response

After the conditioning trials, Albert began to cry and attempt to crawl away when presented with just the rat—evidence that conditioning had taken place. Watson and Rayner then tested whether this fear would generalize to other stimuli with similar characteristics.

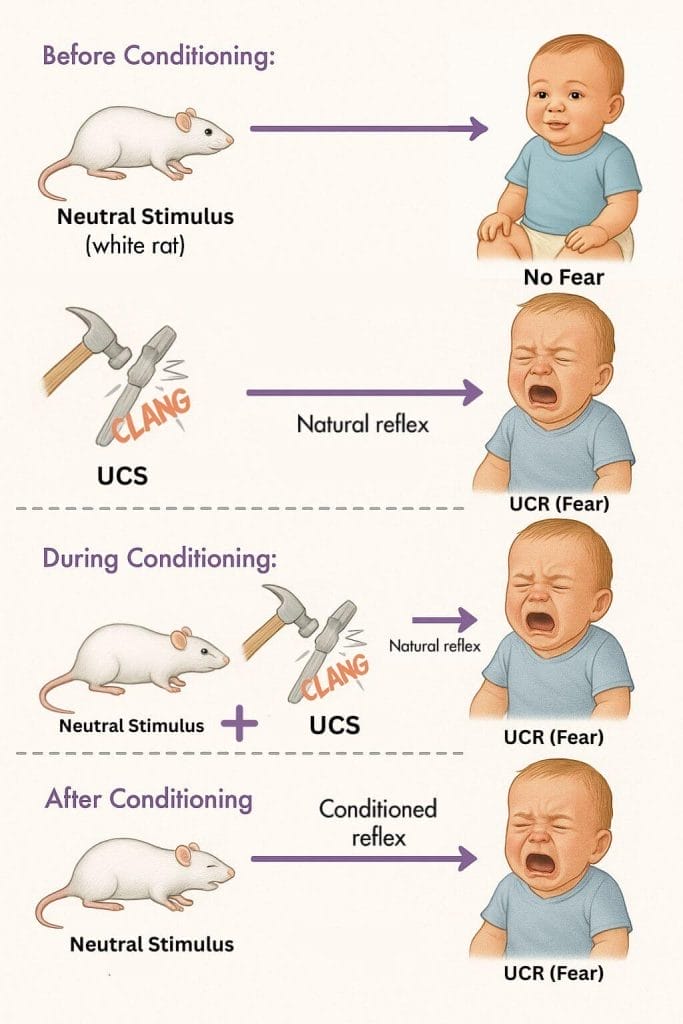

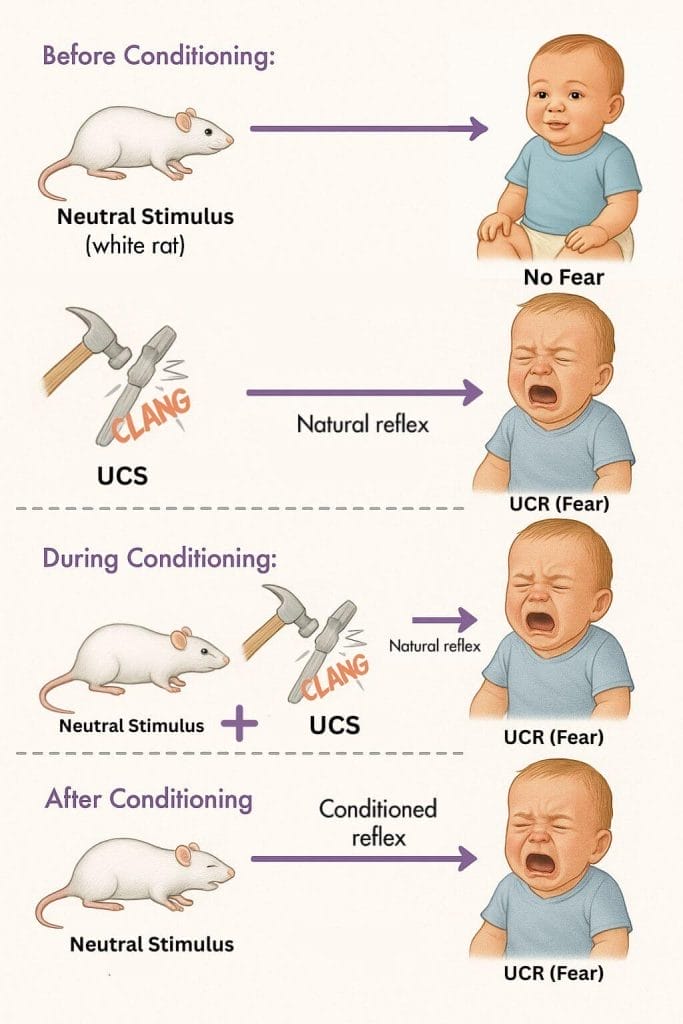

STUDENT TASK: CONDITIONING DIAGRAM

Create a visual diagram of the Little Albert conditioning process using these elements:

BEFORE CONDITIONING:

- Neutral Stimulus (white rat) → No fear response

- Unconditioned Stimulus (loud noise) → Unconditioned Response (fear)

DURING CONDITIONING:

- Neutral Stimulus (white rat) + Unconditioned Stimulus (loud noise) → Unconditioned Response (fear)

AFTER CONDITIONING:

- Conditioned Stimulus (white rat) → Conditioned Response (fear)

This diagram will help you visualize and remember the conditioning process for exams.

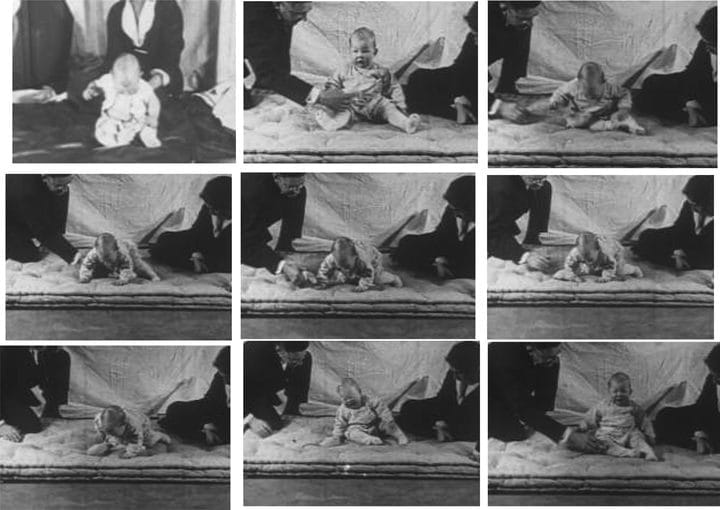

Albert’s responses to a rat across different experimental phases. The initial image represents the baseline observation, while the subsequent images (arranged in sequential order from top left to bottom right) showcase his interactions during the transfer session. These visual records are released under a public domain license.

Classical Conditioning in Action: NS, US, CS and CR Explained

The Little Albert experiment provides a perfect illustration of classical conditioning principles. Understanding these fundamental concepts is crucial for psychology students, as they form the foundation of behavioral learning theory.

Core Classical Conditioning Components

Watson and Rayner’s experiment demonstrated each essential component of classical conditioning:

- Neutral Stimulus (NS): The white laboratory rat was initially neutral for Albert. He showed interest in it and even reached out to touch it with no signs of fear.

- Unconditioned Stimulus (US): The loud noise produced by striking the steel bar was a naturally frightening stimulus that required no prior learning to elicit fear.

- Unconditioned Response (UR): Albert’s natural fear reaction to the loud noise—crying and showing distress—was an unlearned, automatic response.

- Conditioning Process: By repeatedly pairing the rat (NS) with the frightening noise (US), Watson created an association between these stimuli in Albert’s mind.

- Conditioned Stimulus (CS): After conditioning, the previously neutral rat became a conditioned stimulus capable of eliciting fear on its own.

- Conditioned Response (CR): Albert’s learned fear response to the rat—becoming upset and showing avoidance—was the conditioned response.

This process demonstrates how new stimulus-response connections can be formed through learning, which was precisely what Watson aimed to prove.

Why the Little Albert Study Matters for Understanding Conditioning

The Little Albert experiment is particularly valuable for understanding classical conditioning because it shows how:

- Emotional responses (not just physical reflexes) can be conditioned

- Human behavior follows the same conditioning principles as animal behavior

- Fears and phobias can develop through associative learning

- A previously neutral stimulus can acquire the power to elicit strong emotional responses

The Behaviorist Interpretation

For behaviorists like Watson, the Little Albert experiment supported their core belief that:

“Psychology as the behaviorist views it is a purely objective experimental branch of natural science. Its theoretical goal is the prediction and control of behavior.” (Watson, 1913)

By demonstrating that fears could be experimentally induced, Watson believed he had evidence that complex human emotions were simply conditioned responses rather than innate mental states—supporting behaviorism’s focus on observable behavior rather than internal mental processes.

EXAM TIP: COMPARING PAVLOV AND WATSON

| Aspect | Pavlov’s Dogs | Little Albert |

|---|---|---|

| Species | Dogs | Human infant |

| NS→CS | Bell/metronome | White rat |

| US | Meat powder | Loud noise |

| UR/CR | Salivation | Fear response |

| Purpose | Study digestive reflexes | Demonstrate emotional conditioning |

| Significance | Discovered classical conditioning principles | Showed conditioning applies to human emotions |

When answering exam questions, be ready to compare and contrast these landmark studies. Examiners often ask how Watson adapted and applied Pavlov’s principles to human behavior. Read our in-depth article on Ivan Pavlov here.

Results & Findings: How Albert Responded to Conditioning

The results of the Little Albert experiment provided compelling evidence for Watson and Rayner’s conditioning hypothesis, though modern reanalysis has raised questions about the strength and consistency of these findings.

Initial Conditioning Results

After seven pairings of the rat with the loud noise (over two sessions), Albert showed clear signs of fear when presented with the rat alone:

- He began to cry when he saw the rat

- He turned and crawled away rapidly when the rat approached

- Watson reported he “began to crawl away so rapidly that he was caught with difficulty before reaching the edge of the table”

These responses contrasted sharply with Albert’s initial curiosity toward the rat, suggesting successful conditioning had occurred. However, it’s important to note that the intensity of Albert’s response varied across trials.

Strength and Consistency of the Fear Response

A critical examination of the available evidence (including film footage) suggests Albert’s conditioned fear may have been less consistent and pronounced than often portrayed in textbooks:

- Albert sometimes showed only mild distress rather than intense fear

- His responses varied across testing sessions

- When allowed to suck his thumb (a natural soothing behavior), Albert sometimes showed minimal fear response

- Powell and Schmaltz (2021) analyzed film footage and found that Albert’s reactions were less dramatic than described in the published report

This variability raises questions about whether Albert truly developed a phobia (an intense, irrational fear) or simply a milder conditioned response that fluctuated based on context and his emotional state.

Measurement and Documentation Issues

Watson and Rayner’s methods for measuring fear were subjective by modern standards:

- They relied on observational judgments rather than physiological measures

- Their documentation of responses lacked standardized scoring criteria

- The dependent variable (fear response) was not clearly operationalized

These methodological limitations make it difficult to determine precisely how successful the conditioning was and highlight the importance of objective measurement in contemporary research.

MODEL ANSWER EXCERPT: EVALUATING LITTLE ALBERT’S CONDITIONING

“While Watson and Rayner claimed to have successfully conditioned fear in Little Albert, modern reanalysis of film evidence suggests the fear response may have been less robust than originally reported. Albert’s reactions varied across sessions and could be diminished when he was allowed to self-soothe. This inconsistency highlights a key limitation: the study lacked objective measures of fear, relying instead on researchers’ subjective interpretations of Albert’s behavior. This point demonstrates how methodological limitations can affect the validity of even landmark studies in psychology’s history.”

Examiner’s comment: This response effectively evaluates the evidence by pointing to specific issues with measurement and documentation. The student demonstrates critical thinking by not simply accepting the researchers’ claims but considering alternative interpretations based on modern analysis. This approach would earn high marks for AO3 (analysis and evaluation) skills.

Generalization & Extinction: Beyond the Initial Conditioning

The Little Albert experiment went beyond simply conditioning fear of a rat—it also explored two additional classical conditioning principles: generalization and extinction.

Stimulus Generalization

One of Watson and Rayner’s key research questions was whether Albert’s conditioned fear would transfer to other stimuli similar to the white rat. This phenomenon, called stimulus generalization, occurs when a response conditioned to one stimulus transfers to similar stimuli without direct conditioning.

In testing sessions, Albert was exposed to various stimuli to assess generalization:

- A white rabbit

- A dog

- A fur coat

- Cotton wool

- A Santa Claus mask with white cotton beard

- Watson’s hair and observers’ hair

The results showed Albert’s fear did generalize to some degree. According to Watson and Rayner, Albert showed fear responses to:

- The white rabbit (similar in appearance to the rat)

- The dog

- The fur coat

- Cotton wool (which shared the white, furry characteristics of the rat)

However, Albert did not show consistent fear toward Watson’s hair or the Santa Claus mask, suggesting limits to the generalization effect. The generalization appeared strongest for stimuli that most closely resembled the original conditioned stimulus (the white rat) in texture and appearance.

This pattern of findings supported Watson’s theory that phobias might develop through generalization from an initial conditioning experience, potentially explaining why people develop fears of objects similar to those involved in frightening experiences.

Extinction and Spontaneous Recovery

Watson and Rayner also observed evidence of extinction—the weakening of a conditioned response when the conditioned stimulus is repeatedly presented without the unconditioned stimulus.

They noted:

- Albert’s fear response to the rat diminished somewhat over the ten days following initial conditioning

- By the final session (approximately a month after conditioning), the fear response, while still present, had weakened

However, they also found that the fear could be “refreshed” by repeating the original conditioning procedure (pairing the rat with the loud noise). This observation aligns with what we now understand about the persistence of conditioned emotional responses and their resistance to complete extinction.

Unfortunately, Albert and his mother left the hospital the day of the final testing session, preventing Watson and Rayner from studying long-term extinction or attempting to systematically decondition Albert’s fear—a significant ethical concern by modern standards.

MNEMONIC DEVICE: “GREAT” FOR CONDITIONING PRINCIPLES

To remember the key conditioning principles demonstrated in the Little Albert experiment, use the acronym “GREAT”:

- Generalization: Fear spreads to similar stimuli (rat → rabbit, fur coat)

- Reinforcement: Pairing CS+US strengthens the CR

- Extinction: CR weakens when CS presented without US

- Acquisition: Initial learning of stimulus-response association

- Temporal contiguity: CS and US must occur close together in time

This mnemonic device helps you recall all five principles that Watson and Rayner’s study demonstrated, ensuring you can discuss the full range of classical conditioning concepts in exam responses.

Evaluation: Methodological Flaws & Limitations

While the Little Albert experiment is considered a landmark study in psychology, it contains significant methodological limitations that must be critically evaluated. Psychology students should be prepared to analyze these flaws as part of a comprehensive understanding of the research.

Sample Size and Generalizability

The most obvious limitation is the study’s sample size of one participant:

- A single-case design makes it impossible to generalize findings confidently to other children

- Individual differences in temperament, responsiveness, and prior experiences cannot be accounted for

- Albert had been raised in a hospital environment from birth, making him potentially unrepresentative of typical children

- Staff reported Albert was unusually stolid and rarely showed fear or rage, suggesting he may have had an atypical emotional temperament

Experimental Controls and Confounding Variables

Several aspects of the experimental design lacked proper controls:

- No control subject: There was no comparison child who received the same exposures without conditioning

- Pseudoconditioning: The researchers didn’t control for the possibility that the loud noise may have simply sensitized Albert to be fearful of novel stimuli

- Maturation effects: As Albert aged from 9 to 12 months during the study, natural developmental changes could have influenced his responses

- Confounded generalization tests: The researchers conditioned Albert using the same neutral stimuli (rabbit and dog) that they later used to test generalization

- Multiple researcher effects: Watson and Rayner, plus other observers, were all present during testing, potentially influencing Albert’s responses

Measurement Problems

The study also suffered from significant measurement limitations:

- Subjective assessment: There were no objective measures of fear—only the researchers’ interpretations of Albert’s behavior

- Poorly operationalized variables: The dependent variable (fear response) wasn’t clearly defined or measured systematically

- Inconsistent procedures: The testing environment and protocols varied across sessions

- Selective reporting: Watson may have highlighted the most dramatic responses while downplaying instances where conditioning appeared weaker

Modern Reanalysis

Recent scholarly reexaminations have raised additional methodological concerns:

- Powell and Schmaltz (2021) analyzed film footage and found Albert’s reactions were more ambiguous and less consistently fearful than reported

- The film evidence suggests Albert’s responses may have been startled reactions rather than conditioned fear

- Some footage appears edited or rearranged, raising questions about the chronology and authenticity of the recorded responses

EXAM TIP: EVALUATING METHODOLOGY

When discussing the Little Albert study’s limitations in exams, always:

- Identify the specific methodological flaw

- Explain why it’s problematic

- Describe how it impacts the study’s validity or reliability

- Suggest how the issue could have been addressed

For example: “The single-subject design severely limits generalizability because individual differences could explain Albert’s responses. This reduces external validity. A multiple-baseline design with several infants would have strengthened the findings.”

This structured approach demonstrates sophisticated critical thinking that examiners reward with higher marks.

Ethical Issues: Why the Study Couldn’t Be Conducted Today

The Little Albert experiment stands as a prime example of how research ethics have evolved in psychology. By examining its ethical shortcomings, students can understand why such studies would never be permitted in contemporary research.

Informed Consent Violations

One of the most serious ethical breaches involved the lack of proper informed consent:

- Albert’s mother, a wet nurse at the hospital where the research was conducted, was not fully informed about the study’s purpose or procedures

- She was not told that researchers would intentionally frighten her child

- The power dynamic between employer (hospital) and employee (Albert’s mother) created potential for coercion

- No documentation of any consent process exists

Modern ethical standards require fully informed, voluntary consent from participants or their legal guardians, with comprehensive disclosure of all procedures and potential risks.

Causing Harm to a Vulnerable Participant

The study deliberately caused psychological distress to an infant who could not consent or understand:

- Researchers intentionally frightened Albert multiple times, causing him visible distress

- Infants are considered an especially vulnerable population requiring additional protections

- The conditioning may have had unknown long-term psychological effects

- No plan for monitoring potential negative impacts existed

Contemporary ethical guidelines prioritize participant welfare and prohibit procedures likely to cause psychological harm, particularly to vulnerable populations like children.

Lack of Debriefing and Deconditioning

Perhaps most troubling is what happened—or rather, didn’t happen—after the study:

- Watson and Rayner made no attempt to decondition Albert’s fear response

- Albert and his mother left the hospital immediately after the final testing session

- There was no follow-up to assess potential lasting effects of the conditioned fear

- The researchers published their findings with no apparent concern for Albert’s welfare

Today’s ethical standards require researchers to debrief participants, address any negative effects of participation, and ensure participants don’t leave studies worse off than when they began.

The Identity and Fate of Little Albert

The identity and subsequent life of “Little Albert” remained mysterious for decades. Recent historical detective work has uncovered compelling evidence about who Albert really was:

- Beck, Levinson, and Irons (2009) identified “Albert B.” as likely being Douglas Merritte, the son of a wet nurse named Arvilla Merritte who worked at Johns Hopkins

- Further research by Fridlund, Beck, Goldie, and Irons (2012) suggested Douglas had neurological impairments that may have affected his responses

- Tragically, Douglas died at age 6 from hydrocephalus (water on the brain)

- However, Powell, Digdon, Harris, and Smithson (2014) challenged this identification, suggesting Albert was more likely William Albert Barger, who lived a normal life into his 80s

This ongoing historical debate highlights the importance of thorough documentation and follow-up in research—practices that were sadly lacking in Watson and Rayner’s study.

CASE STUDY: COMPARING RESEARCH ETHICS THEN AND NOW

| Ethical Principle | Little Albert Study (1920) | Modern Equivalent Study |

|---|---|---|

| Informed Consent | Minimal or none; mother likely unaware of procedures | Detailed written consent required, with full explanation of procedures and right to withdraw |

| Risk Assessment | No formal assessment of potential psychological harm | Comprehensive risk assessment required; high likelihood of approval rejection |

| Participant Welfare | Deliberately caused distress; no follow-up | Participant welfare prioritized; immediate termination if distress occurs |

| Debriefing | None; conditioning left intact | Full debriefing required; therapeutic intervention if needed |

| Vulnerable Populations | Infant used with minimal protections | Special ethical review required for research with children |

| Scientific Necessity | Could have used dolls or simulation | Must demonstrate scientific value outweighs minimal risks |

This comparison illustrates the dramatic evolution of research ethics over the past century and why studies like Little Albert serve as important cautionary examples in psychological science.

Significance for Psychology: Impact on Behaviorism & Research

Despite its ethical and methodological limitations, the Little Albert experiment had a profound and lasting impact on psychology. Understanding its significance helps students appreciate why this study continues to appear in textbooks a century after it was conducted.

Establishing Human Classical Conditioning

The experiment made several important contributions to psychological science:

- It provided evidence that classical conditioning, previously demonstrated in animals, could also explain human emotional responses

- It suggested that complex emotional reactions like fear could be understood through simple conditioning principles

- It demonstrated that conditioned emotional responses could generalize to similar stimuli

- It supported Watson’s controversial claim that emotional reactions are learned rather than innate

These findings helped establish behaviorism as a dominant force in American psychology for decades to come.

Watson’s Behaviorist Legacy

The Little Albert experiment became powerful evidence for Watson’s behaviorist approach:

- It aligned with his famous assertion that he could take any healthy infant and “train him to become any type of specialist” through conditioning

- It supported his rejection of introspection and mentalistic concepts in favor of observable behavior

- It contributed to the shift away from Freudian and psychodynamic approaches toward more experimentally-based psychology

- It exemplified his belief that psychology should be an objective science focused on predicting and controlling behavior

Watson later leveraged his conditioning research in his influential work on child-rearing, advising parents to condition their children through consistent environmental control rather than showing what he considered excessive affection.

Influence on Understanding Fears and Phobias

The study had particular significance for understanding the development of fears and phobias:

- It provided an experimental model for how specific phobias might develop through conditioning

- It suggested that fears could generalize from one object to similar objects

- It helped explain why people might develop phobias of objects they had never directly experienced as harmful

- It laid groundwork for future behavioral treatments for phobias based on reconditioning principles

This conditioning model of fear acquisition continues to influence clinical approaches to anxiety disorders, though it’s now recognized as only one of several pathways through which fears develop.

Methodological Influence

Despite its flaws, the Little Albert study influenced psychological research methodology:

- It demonstrated the potential of experimental approaches to studying emotions

- It showed how laboratory conditions could be used to study learned emotional responses

- It highlighted the value of systematic observation and documentation of behavior

- It pioneered the use of film to record experimental procedures and outcomes

The study also serves as an instructive example of both the power and limitations of case study designs in psychological research.

EXAM APPLICATION: CONNECTING LITTLE ALBERT TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY

To demonstrate sophisticated understanding in exams, connect the Little Albert study to these areas of modern psychology:

- Clinical Psychology: Explain how exposure therapy for phobias relies on principles of extinction demonstrated in the Little Albert study

- Neuroscience: Discuss how modern neuroimaging studies have identified brain structures involved in conditioned fear (amygdala) that weren’t understood in Watson’s time

- Developmental Psychology: Compare Watson’s environmentalist views with contemporary understanding of temperament and genetic influences on fear responses

- Research Ethics: Analyze how reaction to studies like Little Albert led to the development of institutional review boards and ethical guidelines

Making these connections shows examiners you understand both historical and contemporary relevance—a key to earning top marks.

Exam Success: How to Discuss Little Albert in Your Essays

The Little Albert experiment frequently appears in psychology exams, particularly in questions about learning theory, research ethics, or the history of psychology. This section provides strategic guidance on how to effectively apply your knowledge of the study in exam responses.

Common Exam Questions About Little Albert

Be prepared to address these frequently asked question types:

- Explanation questions: “Describe the Little Albert experiment and explain how it demonstrates classical conditioning principles.”

- Evaluation questions: “Critically evaluate the methodology and findings of Watson and Rayner’s Little Albert study.”

- Ethics questions: “Using the Little Albert experiment as an example, discuss ethical issues in psychological research.”

- Application questions: “How does the Little Albert experiment help explain the development of phobias?”

- Comparison questions: “Compare and contrast Pavlov’s dog experiments with Watson and Rayner’s Little Albert study.”

Structuring Strong Essay Responses

When discussing the Little Albert experiment in essays, follow this effective structure:

- Introduction: Briefly state what the study involved, when and by whom it was conducted, and why it was significant

- Description: Provide accurate details about the methodology, focusing on:

- Participant characteristics

- Experimental procedure

- Key findings

- Application of theory: Explain how the study demonstrates:

- Classical conditioning principles

- Stimulus generalization

- Extinction

- Methodological evaluation: Critically analyze:

- Internal validity issues

- External validity/generalizability limitations

- Measurement problems

- Ethical analysis: Discuss ethical concerns using modern principles:

- Informed consent

- Protection from harm

- Special protections for vulnerable populations

- Significance: Explain the study’s impact on:

- Development of behaviorism

- Understanding of fear acquisition

- Research ethics development

- Conclusion: Summarize the study’s importance while acknowledging its limitations

ESSAY PLANNING TEMPLATE: LITTLE ALBERT STUDY

I. Introduction

□ Watson & Rayner (1920)

□ Johns Hopkins University

□ 9-month-old infant

□ Classical conditioning of fear

II. Methodology

□ Baseline: No fear of rat

□ US: Loud noise

□ CS: White rat

□ Conditioning: 7 pairings over 2 sessions

□ Testing: Rat alone and generalization to similar objects

III. Findings

□ Conditioned fear response to rat

□ Generalization to rabbit, dog, fur coat

□ Some extinction over time

IV. Methodological Evaluation

□ Single subject design

□ Lack of control conditions

□ Subjective measurement

□ Confounded variables

□ Recent reanalysis questions

V. Ethical Issues

□ Informed consent problems

□ Deliberately causing distress

□ No deconditioning

□ Vulnerable participant

□ Modern ethical violations

VI. Significance

□ Support for behaviorism

□ Classical conditioning of emotions

□ Understanding fear acquisition

□ Historical impact on research ethics

VII. Conclusion

□ Landmark despite flaws

□ Changed understanding of emotional development

□ Ethical legacy

Key Terms to Include

Demonstrate your technical understanding by incorporating these key terms accurately:

- Neutral stimulus (NS)

- Unconditioned stimulus (US)

- Unconditioned response (UR)

- Conditioned stimulus (CS)

- Conditioned response (CR)

- Stimulus generalization

- Extinction

- Behaviorism

- Classical/Pavlovian conditioning

- Ethical principles (informed consent, nonmaleficence, beneficence)

- External validity

- Internal validity

- Experimental control

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

Psychology examiners frequently see these errors in discussions of the Little Albert experiment:

- Factual inaccuracies: Misrepresenting the age of Albert, the number of conditioning trials, or what stimuli were used

- Oversimplification: Claiming Albert developed a “phobia” when the evidence suggests a milder conditioned response

- Presentism: Judging the ethics solely by modern standards without acknowledging the historical context

- Overinterpretation: Making claims about long-term effects that weren’t measured

- Underutilizing evaluation: Describing the study without critically analyzing its limitations

- Neglecting significance: Focusing on limitations without acknowledging historical importance

MODEL ANSWER EXCERPT: ETHICAL EVALUATION

“The Little Albert experiment violated numerous ethical principles that guide modern psychological research. Most significantly, there was no informed consent—Albert’s mother was likely unaware her child would be deliberately frightened. As Baumrind (1964) argued in her critique of behaviorist research, the researchers prioritized scientific goals over participant welfare. Furthermore, Watson and Rayner made no attempt to decondition Albert’s fear before he left the hospital, potentially leaving him with lasting negative associations. This case illustrates why contemporary ethics requires both protection from harm during studies and appropriate debriefing afterward. Today, institutional review boards would reject any proposal to condition fear in infants, demonstrating how ethical standards have evolved to prioritize participant welfare over knowledge acquisition when the two conflict.”

Examiner’s comment: This response demonstrates sophisticated ethical analysis by identifying specific ethical violations, linking them to broader ethical principles, citing relevant critical perspectives, and making explicit comparisons to modern standards. The student shows awareness of both historical context and contemporary implications—exactly what examiners look for in high-scoring responses.

Remember that psychology examiners reward critical thinking, accurate application of concepts, and balanced evaluation rather than simple description. By structuring your answers using the guidance above, you’ll demonstrate the sophisticated understanding required for top marks when discussing this landmark but controversial study.

Conclusion: The Lasting Legacy of the Little Albert Study

The Little Albert experiment stands as both a landmark in the history of psychology and a profound cautionary tale about research ethics. Watson and Rayner’s study successfully demonstrated that emotional responses—specifically fear—could be classically conditioned in humans, supporting the behaviorist claim that environmental factors shape behavior. The experiment showed how a previously neutral stimulus could acquire the power to elicit fear through association with an unconditioned stimulus, and how this fear could generalize to similar objects.

However, the study’s scientific contributions cannot be separated from its serious methodological and ethical shortcomings. The single-subject design, lack of proper controls, subjective measurements, and failure to decondition Albert’s fear response all undermine its scientific validity by modern standards. More troublingly, the deliberate causing of distress to an infant without informed consent or follow-up care represents a stark violation of contemporary research ethics.

For today’s psychology students, the Little Albert experiment offers valuable lessons on multiple levels. It illustrates fundamental conditioning principles while simultaneously demonstrating how psychological science has evolved—not just in its theoretical understanding, but in its methodological rigor and ethical standards. The study’s controversial legacy continues to spark discussion about the balance between scientific advancement and participant welfare, a tension that remains relevant in psychological research today.

Perhaps the most important lesson from Little Albert is how psychological science can progress through critical reflection on its own practices. The ethical shortcomings that seem so obvious today weren’t widely recognized in Watson’s era, highlighting how ethical awareness in science evolves alongside theoretical knowledge. By studying this flawed but influential experiment, students gain insight into both the foundational concepts of behavioral psychology and the ongoing responsibility of researchers to conduct studies that respect human dignity and welfare.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Was the Little Albert Experiment?

The Little Albert experiment was a famous psychological study conducted in 1920 by John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner. It demonstrated that emotional responses (specifically fear) could be classically conditioned in humans. The researchers conditioned a 9-month-old boy called “Little Albert” to fear a white rat by repeatedly pairing its appearance with a frightening loud noise. The study showed how previously neutral stimuli could become fear-inducing through association.

Who Was Little Albert?

“Little Albert” was the pseudonym given to the infant subject in Watson and Rayner’s conditioning experiment. Historical research suggests he was most likely William Albert Barger, the son of a wet nurse working at Johns Hopkins University Hospital. An alternative theory proposed he was Douglas Merritte, who later died at age 6 from hydrocephalus. The true identity remains debated, though recent evidence favors the Barger identification (Powell et al., 2014).

What Happened to Little Albert After the Experiment?

If Little Albert was William Albert Barger (the most likely identification), he lived a normal life into his 80s, dying in 2007 without knowing he was the famous subject. Watson and Rayner never conducted follow-up studies because Albert and his mother left the hospital immediately after the final testing session. Importantly, the researchers never deconditioned Albert’s fear response before the study ended, raising serious ethical concerns about potential lasting psychological effects.

Was the Little Albert Experiment Ethical?

No, by modern standards, the Little Albert experiment violated multiple ethical principles. The researchers did not obtain proper informed consent from Albert’s mother, deliberately caused psychological distress to an infant, and failed to decondition the fear response they had created. The study used a vulnerable participant who could not consent, with no apparent concern for his welfare. Today, such research would never receive approval from institutional review boards or ethics committees.

Did Little Albert Develop a Phobia?

While often described as developing a phobia, evidence suggests Albert developed a milder conditioned fear response rather than a true phobia. Recent analysis of film footage by Powell and Schmaltz (2021) indicates his responses were less consistent and intense than typically portrayed in textbooks. Albert sometimes showed only mild distress when presented with the rat, especially when allowed to self-soothe by sucking his thumb. The reaction appears more like startle or wariness than a clinical phobia.

How Did the Little Albert Study Demonstrate Classical Conditioning?

The Little Albert experiment demonstrated classical conditioning by showing how a neutral stimulus (white rat) could become a conditioned stimulus capable of eliciting fear. Initially, Albert showed no fear of the rat. After repeated pairings with a frightening loud noise (the unconditioned stimulus), the rat alone began to elicit fear (the conditioned response). The study further demonstrated stimulus generalization when Albert showed fear toward similar furry objects like rabbits and fur coats.

Why Is the Little Albert Experiment Important in Psychology?

The Little Albert experiment is important for several reasons: it provided early evidence that human emotions could be conditioned through associative learning; it supported behaviorism’s claim that environmental factors shape behavior; it demonstrated principles like stimulus generalization and extinction in humans; and it contributed to understanding how fears and phobias might develop. Its ethical violations also played a role in the development of research ethics guidelines that protect participants today.

What Were the Main Criticisms of the Little Albert Study?

The main criticisms include: poor experimental design (single subject, no control group); inadequate measurement (subjective assessments of fear); confounding variables (maturation effects as Albert aged); ethical violations (causing distress without consent); lack of follow-up or deconditioning; and questionable interpretation of results. Modern reanalysis of film footage suggests Albert’s fear responses may have been less dramatic and consistent than Watson reported, raising questions about the strength of the conditioning effect.

What Was Watson’s Theory Behind the Little Albert Study?

Watson conducted the Little Albert experiment to support his behaviorist theory that all human behavior—including emotional responses—is learned through conditioning rather than being innate. He believed he could experimentally demonstrate that fears are acquired through environmental associations, not inherited. This aligned with his famous (and controversial) claim that he could take any healthy infant and train them to become any type of specialist regardless of their natural tendencies or talents.

How Did the Little Albert Study Change Psychology?

The Little Albert study helped establish behaviorism as a dominant force in American psychology for decades. It shifted focus from introspection to observable behavior, demonstrated that emotional responses could be studied experimentally, and provided a model for understanding fear acquisition that influenced theories of anxiety disorders. It also ultimately contributed to the development of modern research ethics by illustrating practices that are now recognized as harmful and unacceptable in psychological science.

References

- Baumrind, D. (1964). Some thoughts on ethics of research: After reading Milgram’s “Behavioral study of obedience.” American Psychologist, 19(6), 421-423.

- Beck, H. P., Levinson, S., & Irons, G. (2009). Finding Little Albert: A journey to John B. Watson’s infant laboratory. American Psychologist, 64, 605-614.

- Buckley, K. W. (1989). Mechanical man: John Broadus Watson and the beginnings of behaviorism. Guilford Press.

- Fridlund, A. J., Beck, H. P., Goldie, W. D., & Irons, G. (2012). Little Albert: A neurologically impaired child. History of Psychology, 15, 1-34.

- Goodwin, C. J. (2015). A history of modern psychology (5th ed.). Wiley.

- Harris, B. (2011). Letting go of Little Albert: Disciplinary memory, history, and the uses of myth. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 47(1), 1-17.

- Powell, R. A., Digdon, N., Harris, B., & Smithson, C. (2014). Correcting the record on Watson, Rayner, and Little Albert: Albert Barger as “psychology’s lost boy.” American Psychologist, 69, 600-611.

- Powell, R. A., & Schmaltz, R. M. (2021). Did Little Albert actually acquire a conditioned fear of furry animals? What the film evidence tells us. History of Psychology, 24(2), 164-179.

- Tomarken, A. J., Mineka, S., & Cook, M. (1989). Fear-relevant selective associations and covariation bias. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 98(4), 381.

- Watson, J. B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist views it. Psychological Review, 20, 158-177.

- Watson, J. B. (2017). Behaviorism. Routledge.

- Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3(1), 1-14.

Further Reading and Research

Recommended Articles

- Harris, B. (2011). Letting go of Little Albert: Disciplinary memory, history, and the uses of myth. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 47(1), 1-17.

- Powell, R. A., & Schmaltz, R. M. (2021). Did Little Albert actually acquire a conditioned fear of furry animals? What the film evidence tells us. History of Psychology, 24(2), 164-179.

- Fridlund, A. J., Beck, H. P., Goldie, W. D., & Irons, G. (2012). Little Albert: A neurologically impaired child. History of Psychology, 15(4), 302-327.

Suggested Books

- Watson, J. B. (2017). Behaviorism. Routledge.

- Watson’s classic text outlining his behaviorist approach, providing context for understanding his motivations in the Little Albert study.

- Buckley, K. W. (1989). Mechanical man: John Broadus Watson and the beginnings of behaviorism. Guilford Press.

- A comprehensive biography of Watson that examines his personal life, career, and contributions to psychology, including detailed coverage of the Little Albert experiment.

- Goodwin, C. J. (2015). A history of modern psychology (5th ed.). Wiley.

- Places the Little Albert experiment in historical context within the development of psychology as a science, with an excellent discussion of behaviorism’s rise.

Recommended Websites

- Simply Psychology

- Offers a detailed explanation of the Little Albert experiment with diagrams explaining classical conditioning, evaluation points, and learning resources for students.

- American Psychological Association

- Provides historical articles about Watson, ethics in research, and the evolution of psychological science, including retrospectives on controversial studies.

- PBS Frontline: “The American Experience: A Science Odyssey”

- Features a section on Watson’s work and behaviorism with video clips, historical photographs, and educational materials about the Little Albert experiment.